Optic Nerve Sheath Meningioma

By Paul T. Finger, MD

Orbital and optic nerve meningioma can extend from the brain into the orbit (behind the eye) and push the eye forward causing a bulging of the eye called proptosis. Though rare, when they occur, they are a significant cause of vision loss.

Symptoms

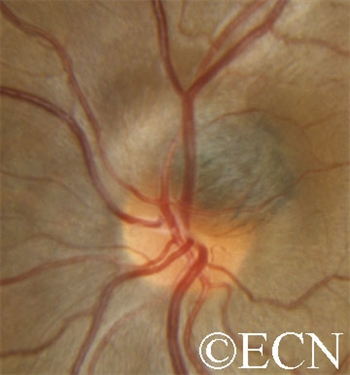

Patient with orbital meningioma typically have proptosis (bulging eye). Optic nerve compression can cause optociliary shunt vessels to form, as well as loss of vision. Depending on the location, size and degree of optic nerve involvement; patients can develop monocular and/or junctional defect is the patients field of vision.

Diagnosis

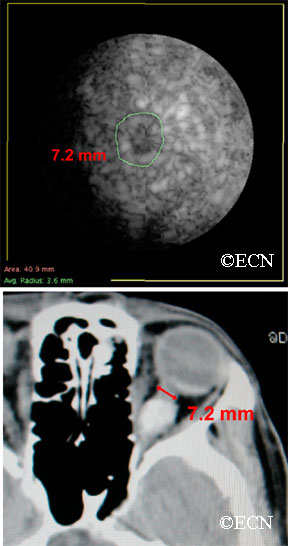

Patients usually present in their 40s and may have neurofibromatosis type 2. In making this diagnosis, one should look for the triad of vision loss, optic atrophy and abnormal vessels on the optic nerve. The nerve head can appear raised. Enlarged blood vessels are called “optociliary shunt vessels” and indicated that the meningioma has disrupted the natural circulation through the optic nerve to the retina and choroid. Angiography of the optic nerve head will clearly demonstrate the abnormal blood vessels. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasonography and computed tomographic (CT) imaging have been used to evaluate the orbital tumor and measure the optic nerve sheath diameter. CT is particularly helpful for imaging calcium within the tumor.

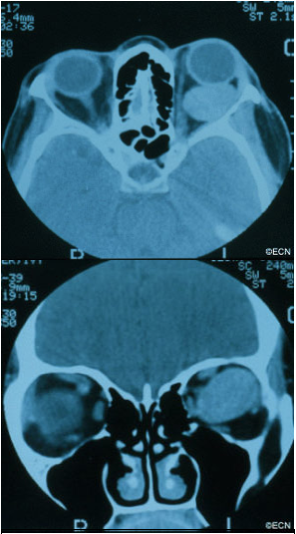

Computed tomography (CT) shows that the eye is pushed forward by this optic nerve sheath meningioma. Notice that the tumor is relatively bright (radio-dense). Imaging of the brain can determine if the meningioma extends into the brain.

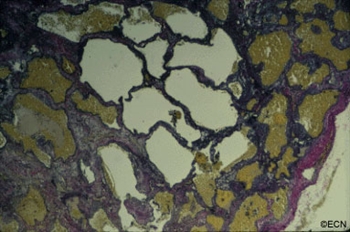

In the images above, note that computed tomography of this optic nerve sheath meningioma. C demonstrates the calcific density of the left optic nerve. An x-ray film shows the linear density (seen on the right side of the film crossing the inferior orbital rim) which corresponds to the optic nerve sheath meningioma seen above.

Treatment Plan

Orbital meningioma is typically a slow-growing tumor. Once diagnosed, meningioma can be observed for growth prior to considering intervention. Treatment is indicated when there is a risk of spread to the central nervous system (in primary optic nerve sheath meningioma), documented progressive vision loss, or for rapid growth.

Computed tomography of the optic nerve sheath meningioma. Note the almost calcific density of the left optic nerve. An x-ray film shows the linear density (seen on the right side of the film crossing the inferior orbital rim) which corresponds to the optic nerve sheath meningioma seen above.

Though microsurgical resections have been tried (in an effort to spare the optic nerve), most eventually fail. The goal of local resection should be complete removal of the meningioma. This usually involves removal of the involved optic nerve. If complete surgical removal is not possible or in special circumstances, radiation therapy is commonly employed.

Biopsy:

Indications for biopsy include: atypical tumors, aggressive disease, acute vision loss and when a pathology diagnosis is requested. Certain inflammatory tumors can have a similar appearance to orbital meningiomas. However, biopsy carries risk for vision loss.

Treatment:

Orbital meningioma is typically a slow-growing tumor. One must consider patient age, rate of tumor growth and risk for loss of vision. That said, once diagnosed slow or non-growing meningiomas can be observed for further growth or stabilization prior to considering intervention. In general, treatment is indicated when there is a risk of spread to the central nervous system (in primary optic nerve sheath meningioma), documented progressive vision loss, or for rapid growth.

Treatment alternatives are tailored to the clinical situation. For example, if vision is lost, the tumor is growing toward the central nervous system and is resectable; it is removed. If complete surgical removal is not possible or in special circumstances, microsurgical resection or external beam radiation therapy can be considered. These decisions are complex and best made with your neuro-ophthalmologist, neurologist and orbital surgeon.