Choroidal Melanoma Affecting the Optic Nerve

By Paul T. Finger, MD

Description

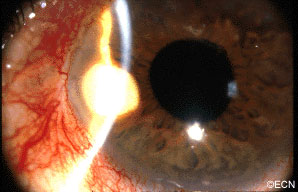

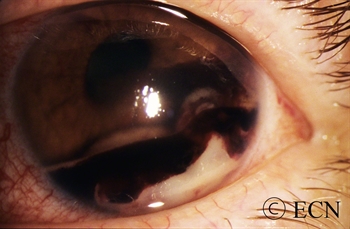

Choroidal melanoma can grow near, touch and even cover the optic nerve. Like other choroidal melanomas, they can exhibit orange pigment on its surface, subretinal fluid (localized retinal detachment), and thickness. The choroidal melanoma in the next photograph exhibits all three findings.

Choroidal melanoma can grow near, touch and even cover the optic nerve. Like other choroidal melanomas, they can exhibit orange pigment on its surface, subretinal fluid (localized retinal detachment), and thickness. The choroidal melanoma in the next photograph exhibits all three findings.

Symptoms

Juxtapapillary choroidal melanoma is typically near the central macular retina and may cause symptoms. Unlike most patients with choroidal melanoma, when the optic nerve is affected patients will have complaints of decreased vision, visual field defects, flashing lights or floaters (spots). However, most choroidal melanomas are found on routine eye examination with dilated ophthalmoscopy.

Diagnosis

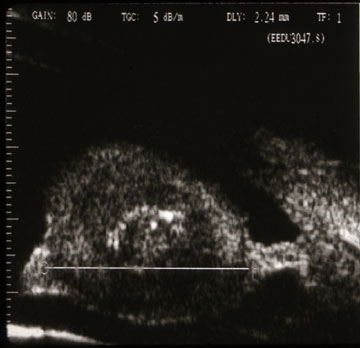

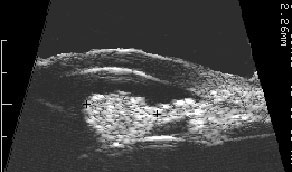

Choroidal melanoma that affects the optic nerve must be differentiated from optic nerve melanocytoma. The eye care specialist will examine the tumor for evidence of orange pigment (lipofuscin, melanolipofuscin), thickness (as measured by ultrasound), for leakage (as measured by photography with angiography), and with optical coherence tomography (OCT).

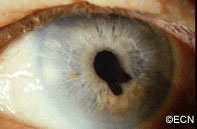

Unlike optic nerve melanocytoma, malignant choroidal melanoma does not typically spread-out along the nerve fiber layer and are lighter in color. In addition, melanocytoma-OCT findings can be particularly helpful showing tumor cell invasion of the overlying retina and vitreous. In either case, it can be difficult to determine the diagnosis of very small tumors. In these cases, the tumor can be closely watched “followed” for evidence of growth, then a biopsy may need be performed. Dr. Finger has found that melanomas that completely encircle the optic disc (circumpapillary) are likely to cause an afferent pupillary defect.

Treatments

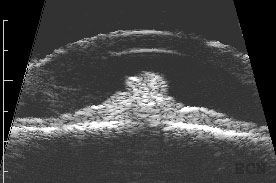

Choroidal melanoma that encircles or covers the optic nerve are particulary difficult to treat with eye-sparing plaque radiation therapy. This is because the optic nerve widens as it leaves the eye into the orbit. In addition, it becomes encased in the optic nerve sheath. Dr. Fingers’ 3D ultrasound studies showed that the nerve nearly triples in diameter behind the eye. Therefore, if a plaque is perfectly placed on the back of the eye, it can only reach to 1.5 mm from the optic disc (effectively missing the rest of the uncovered melanoma. This is why, many patients with melanomas touching or surrounding the optic disc were treated by removal (enucleation) of the affected eye.

Now with 12-years follow up, 94% of patients with choroidal melanoma do not have to lose their eye. For those tough to peripapillary, juxtapapillary and even circumpapillary melaoma, Dr. Finger invented 8-mm slotted plaques. The slot accomodated the entire optic nerve sheath into the plaque, thus allowing the plaque radiation to completely cover and surround the cancer. Fingers’ Slotted Plaques have been able to control more than 98% of these melanomas, has been able to spare some vision (with subsequent intensive anti-VEGF therapy) and allow patients to keep their eye. The patient must be counseled that they are at risk for impaired vision in the irradiated eye.