Ocular Melanoma Mystery: Rare Eye Cancer Found in 36 Auburn University Graduates

With 87,110 diagnoses estimated to be made in 2018 for U.S. Americans, skin cancer, particularly a melanoma, is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in the United States. Ocular melanomas, however, remain uncommonly diagnosed, affecting just six in every one million people a year. Given the extreme rarity of ocular melanomas, doctors and researchers were shocked to find this disease found in highly concentrated numbers in two states. A total of 36 people — all graduates from Auburn University, Alabama — were diagnosed with ocular melanoma. From Huntersville, North Carolina, 18 patients were also found out to have the same disease.

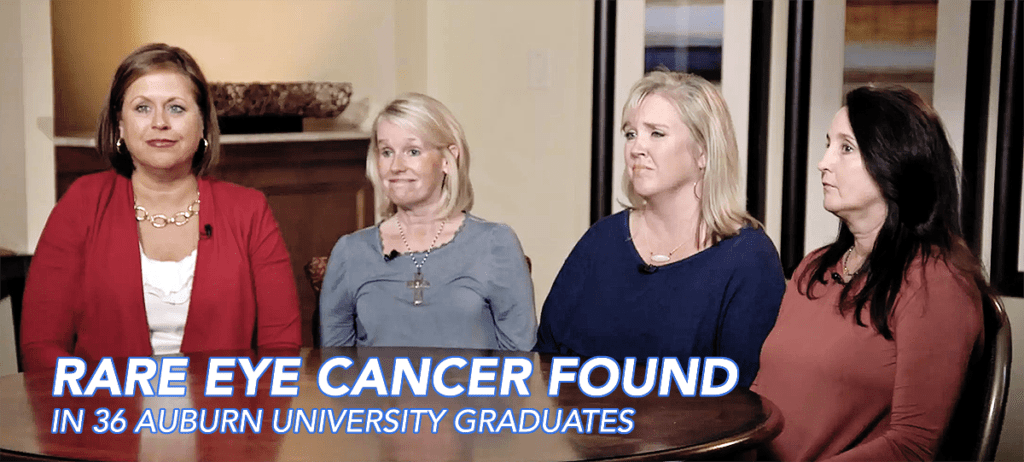

Juleigh Green, Allison Allred, and Ashley McCrary had spent their years at Auburn University as close friends. And later on in their lives, each woman discovered they had the same rare disease. Juleigh Green was the first among her friends to be diagnosed. Just 27 at the time, Green was experiencing strange flashes of light obstructing her vision and consulted her ophthalmologist immediately. In an interview with CBS, Green explains her shock upon what they found:

“[My doctor] said, ‘There’s a mass there, there’s something there, I don’t know what it is, but it looks like it could be, you know, a tumor,’” Green said. “It’s like you had the breath knocked out of you, you know?”

Allison Allred, who also was experiencing flashes of light for 7 to 10 days, was the second of their friend circle to be diagnosed in 2001, at the age of 31. Her doctor had first believed that the flashes were due to a retinal detachment. According to Allred, her doctor had said: “Well, [the retina] is detached because there’s a 10 millitmeter melanoma sitting on it.”

Both Green and Allred opted for enucleation and have had their afflicted eye removed. However, Allred’s extremely aggressive and stubborn cancer has since recurred nine times in six separate places in her body. “Two days ago I found out that it’s come back to my brain,” Allred told CBS, “So, I’m actually gonna have radiation on my brain tomorrow.”

Ashley McCracy was the third friend, with her own diagnosis coming from observing unusual black spots along her iris. In an interview with CBS News correspondent Anna Werner, McCrary said:

“What’s crazy is literally standing there, I was like, ‘Well, I know two people who’ve had this cancer.”

“And did you understand then how strange that was?” asked Werner.

“No. No, I didn’t.”

All three women were treated at Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. McCrary mentioned Green and Allred’s similar diagnosis to her oncologist at Kimmel Center, Dr. Marlana Orloff.

Orloff was baffled.

“Most people don’t know anyone with this disease,” Orloff said. “We said, ‘OK, these girls were in this location, they were all definitively diagnosed with this very rare cancer — what’s going on?”

A fourth Auburn alumna, Lori Lee, is also being treated at Kimmel Center. “This is a rare cancer, so it’s not like you can just go anywhere and have anybody know anything really about it,” Lee said. “Until we get more research into this, then we’re not gonna get anywhere. We’ve got to have it so that we can start linking all of them together to try and find a cause, and then one day, hopefully, a cure.”

Orloff and her fellow researchers and oncologists at Kimmel Center immediately began to investigate this bizarre case. Thus far, the Alabama Department of Health states that “it would be premature to determine that a cancer cluster exists in the area”. Officials at Auburn University hope that research will help illuminate the cause of this rare cancer appearing at such high concentrations in Alabama and North Carolina.

Each patient’s emotional response to this mystery cannot be understated. “That was very hard for me,” McCrary told CBS. “Growing up, the one thing that I liked about myself was my eyes.”

McCrary’s personal journey in dealing with her cancer diagnosis lead to the creation of the Auburn University Ocular Melanoma Page on Facebook, which has astoundingly discovered 36 more graduates afflicted with ocular melanoma. The Facebook Page offers itself as an effective support network for these graduates.

Kimmel Center researchers continue to look for answers to explain these phenomena both in Alabama and North Carolina.

Stay tuned for the latest updates on this case and others by keeping eyecancer.com in your bookmarks.