Treating eye cancer patients in their 80s, 90s, and even older, present a unique set of physical and ethical challenges. A case report written by Dr. Carina Sanvicente and Dr. Paul Finger, and published in the November issue of EyeNet, demonstrates how successful treatment can improve quality of life even for patients of advanced age.

Demographically, America is getting older, and the fastest growing cohort in the country is the “extreme elderly,” that is patients 85 and older. According to agingstats.gov, the “extreme elderly” patient population will rise from 6.2 million in 2014 to 19 million in 2050.

Some of the challenges doctors face when treating eye cancer patients over 85 include other chronic illnesses, their mental state, hearing loss, and mobility issues. For older patients with many other health problems, doctors have to weigh the risks and benefits of treatment, and consider carefully how it will impact their overall quality of life.

Dr. Neil Bressler, Chief of the Retina Division at the Wilmer Eye Institute in Baltimore, said “no one is too old to benefit from treatment, and patients in their 90s could live another 5 to 10 years.” This may seem counter-intuitive. It’s easy to look at an extremely old patient and think maybe treating eye cancer isn’t the highest priority. After all, they are near the end of their lives.

While doctors should certainly consider all of the relevant factors, the case study presented by Drs. Finger and Sanvicente reveals just how beneficial eye cancer treatment can be, even for patients of advanced age.

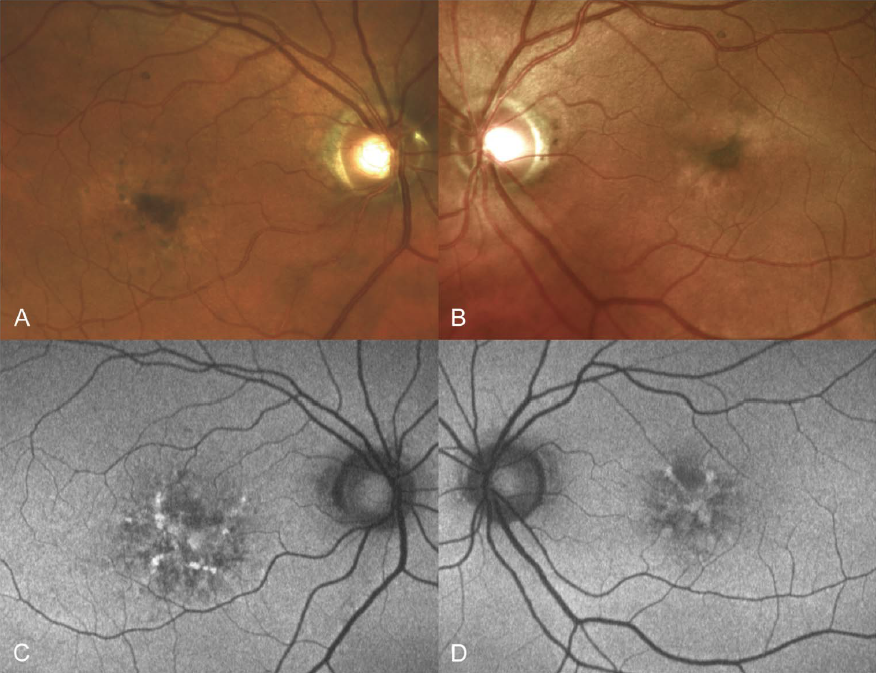

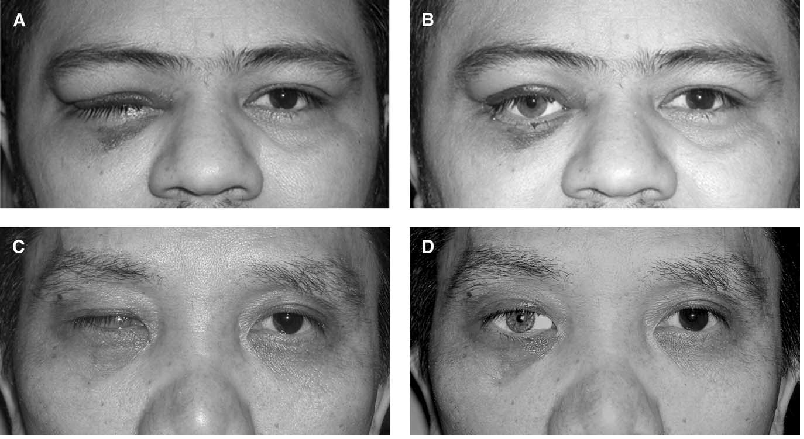

The report focused on Mrs. Gisela Dollinger, a healthy 92-year-old Holocaust survivor who was referred to the New York Eye Cancer Center for treatment of a choroidal melanoma in her left eye. Initially, Dollinger was reluctant to pursue intervention.

“I’m 92, I don’t feel anything; how long do you expect me to live?” she asked.

When Dr. Finger explained she could live another 10 years with good vision in the treated eye, and that forgoing treatment could lead to metastatic melanoma, she relented. She gave consent to undergo palladium-103 plaque brachytherapy .

As Dr. Sanvicente put it, the results surpassed all expectations.

Of course, every patient is different. Not every case involving elderly patients will be as easily resolved. Dr. Finger emphasizes that the key is individualizing care.

“Cases like Mrs. Dollinger’s will likely become more prevalent as our population grows older, and we, as physicians, must be prepared. In this particular case, we had an autonomous, lucid, 92-year-old woman presenting with a life- and sight-threatening condition. She was treated with a safe intervention.”

You can download and read the Mrs. Dollinger’s Full Story Here.