Dr. Finger is a Principal Investigator in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group

Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Publications: Peer-review papers only.

1. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Accuracy of diagnosis of choroidal melanomas in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS Report No. 1. Arch Ophthalmol 108:1268-1273, 1990.

2. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Complications of enucleation surgery. COMS Report No. 2. In: Proceedings of the Symposium on Retina and Vitreous (Rudolph M. Franklin, ed.). New Orleans Academy of Ophthalmology. Kugler Publications, New York, 1993; pp. 181-190.

3. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Design and methods of a clinical trial for a rare condition: The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS Report No. 3. Controlled Clin Trials 14:362-391, 1993.

4. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Mortality in patients with small choroidal melanoma. COMS Report No. 4. Arch Ophthalmol 115:886-893, 1997.

5. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Factors predictive of growth and treatment of small choroidal melanoma. COMS Report No. 5. Arch Ophthalmol 115:1537-1544, 1997.

6. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Histopathologic characteristics of uveal melanomas in eyes enucleated from the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS Report No. 6. Am J Ophthalmol 125:745-766, 1998.

7. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Sociodemographic and clinical predictors of participation in two randomized trials: Findings from the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS Report No. 7. Controlled Clin Trials 22:526-537, 2001.

8. Grossniklaus HE, Albert DM, Green WR, Conway BP, Hovland KR for the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Clear cell differentiation in choroidal melanoma. COMS Report No. 8. Arch Ophthalmol 115:894-898, 1997.

9. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of pre-enucleation radiation of large choroidal melanoma. I: Characteristics of patients enrolled and not enrolled. COMS Report No. 9. Am J Ophthalmol 125:767-778,1998.

10. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of pre-enucleation radiation of large choroidal melanoma. II. Initial mortality findings. COMS Report No. 10. Am J Ophthalmol 125:779-796,1998.

11. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of pre-enucleation radiation of large choroidal melanoma. III. Local complications and observations following enucleation. COMS Report No. 11. Am J Ophthalmol 126:362-372, 1998.

12. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Echography (ultrasound) procedures for the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS Report No. 12. J Ophth Nurs Technol Part I, 18(4):143-149, Part II, 18(5):219-232, 1999.

13. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Consistency of observations from echograms made centrally in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS Report No. 13. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 9:11-27, 2002.

14. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Cause-specific mortality coding: Methods in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS Report No. 14. Control Clin Trials 22: 248-262, 2001.

15. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Assessment of metastatic disease status at death in 435 patients with large choroidal melanoma in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS Report No. 15. Arch Ophthalmol 119:670-676, 2001.

16. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of I-125 brachytherapy for medium choroidal melanoma. I. Visual acuity after 3 years. COMS Report No. 16. Ophthalmology 108(2):348-366, 2001.

17. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma. II. Characteristics of patients enrolled and not enrolled. COMS Report No. 17. Arch Ophthalmol 119: 951-965, 2001.

18. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma. III. Initial mortality findings. COMS Report No. 18. Arch Ophthalmol 119: 969-982, 2001.

19. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma. Local treatment failure and enucleation in the first 5 years after brachytherapy. COMS Report No. 19. Ophthalmology 198:2197-2206, 2002.

20. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Trends in size and treatment of recently diagnosed choroidal melanoma, 1987-1997. Findings from patients evaluated at Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study centers. COMS Report No. 20. Arch Ophthalmol 121:1156-1162, 2003.

21. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Comparison of clinical, echographic, and histologic measurements from eyes with medium-sized choroidal melanoma in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS Report No. 21. Arch Opthalmol 121:1163-1171, 2003.

22. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Ten-year follow-up of fellow eyes of patients enrolled in Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trials. COMS Report No. 22. Ophthalmology 111:996-976, 2004.

23. Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, Caldwell R, Cumming K, Earle JD, Green DL, Hawkins BS, Hayman I, Jaiyesimi I, Kirkwood JM, Koh W-J, Robertson DM, Shaw JM, Thoma J. Screening for metastasis from choroidal melanoma: Experience of the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Report No. 23. Am J Clin Oncol 22:2438-2444, 2004.

24. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of pre-enucleation radiation of large choroidal melanoma. IV. Ten-year mortality findings and prognostic factors. COMS Report No. 24. Am J Ophthalmol 138:936-951, 2004.

25. Melia BM, Moy CS, McCaffrey L: Quality of life in patients with choroidal melanoma: A pilot study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 6:19-28, 1999.

26. COMS Quality of Life Study Group: Quality of life assessment in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study: Design and methods. COMS-QOLS Report No. 1. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 6:5-17, 1999.

27. COMS Quality of Life Study Group: Development and validation of disease-specific measures for choroidal melanoma. COMS-QOLS Report No. 2. Arch Ophthalmol 121:1010-1020, 2003.

28. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Quality of Life Study Group. Quality of life after iodine 125 brachytherapy versus enucleation for choroidal melanoma: 5-year results from the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study prospective study. COMS-QOLS Report No. 3. Arch Ophthalmol (under revision for resubmission, July 2004).

29. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) randomized trial of pre-enucleation radiation of large choroidal melanoma. IV. Ten-year Mortality findings and prognostic factors. COMS Report No. 24. Am J Ophthalmol 138:936-951, 2004.

30. Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group: Second Primary Cancers after Enrollment in the COMS Trials for Treatment of Choroidal Melanoma. COMS Report No. 25. Archives of Ophthalmology 2005:123:601-4.

Related Links

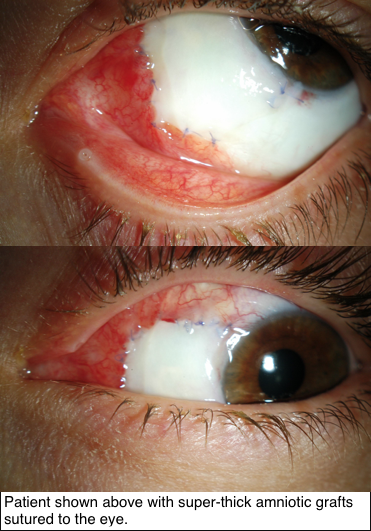

Research supported by The Eye Cancer Foundation has proved greater efficacy of this new technique in recreating the outer surface of the eye and inner surface of the eyelids. As published in the American Journal of Ophthalmology on November 2018, tumors of the conjunctiva and eyelids were surgically removed, then amniotic membranes from donor human placentas were sewn into the defects to recreate a normal ocular and inner eyelid surface.

Research supported by The Eye Cancer Foundation has proved greater efficacy of this new technique in recreating the outer surface of the eye and inner surface of the eyelids. As published in the American Journal of Ophthalmology on November 2018, tumors of the conjunctiva and eyelids were surgically removed, then amniotic membranes from donor human placentas were sewn into the defects to recreate a normal ocular and inner eyelid surface.