A study recently published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology showed revamping multi-drug chemotherapy for retinoblastoma to include tropotecan maintained high cure rates while preserving vision and reducing the risk of treatment related leukemia.

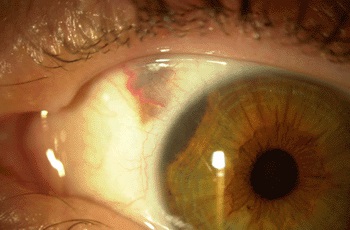

Retinoblastoma ranks as the most common intraocular childhood cancer. It affects approximately 300 children in the United States each year and more than 8,000 worldwide. Better than 96% of patients in North America and Europe are cured of retinoblastoma due to early detection and treatment.

Multi-modal chemotherapy has proved to be an effective treatment, but the widely used triple-drug therapy includes etoposide, a drug that has been associated with secondary acute myeloid leukemia in some patients.

Ten years ago, Michael Dyer, Ph.D., chair of the St. Jude Department of Developmental Neurobiology, began laboratory research seeking a safer retinoblastoma therapy. Researchers began looking at topotecan because it had shown promise in the treatment of other solid tumors.

Working with retinoblastoma tumor cells grown in the laboratory and in mice, Dyer confirmed topotecan could possibly replace etoposide in retinoblastoma therapy and determined the effective dose. The laboratory findings led to a clinical trial including 26 children diagnosed with advanced, bilateral retinoblastoma that had not spread beyond their eyes.

In the trial, triple drug chemotherapy replacing etoposide with topotecan outperformed the standard chemotherapy treatment. Of the 51 diseased eyes included in the study, 78% of those treated with therapy including topotecan were salvaged. That compares to previous reports of 30 to 60% following chemotherapy that included etoposide and often required salvage radiation therapy.

Altogether, 10 eyes had to be surgically removed, including one eye removed at diagnosis prior to chemotherapy and three removed after radiation therapy failed to stop disease progression.

“Preservation of an eye is not synonymous with preservation of vision,” first and corresponding study author Rachel Brennan, M.D. said. “But this therapy provided significant improvement in survival of eyes and useful vision in patients with advanced retinoblastoma.”

Post-treatment vision screening of survivors identified 18 patients with vision of 20/40 or better in at least one eye.

“This 10-year follow-up study shows for the first time that topotecan can be used in front-line therapy to help reduce exposure of retinoblastoma patients to etoposide,” Brennan said first. “We expected patients to be cured, but we also found more than 80 percent of patients had measurable vision.”

The results of the study seem promising. Topotecan may well provide an alternative therapy that maintains or even exceed the effectiveness of traditional multi-modal chemotherapy for retinoblastoma while eliminating one potentially deadly treatment side-effect.